By Jean Redstone

Here’s a piece of info you likely do not know. It will not change your life to know it, but here it goes anyway. In Old English, as in across-the-pond-and-centuries-ago Old English, the chubby, fuzzy familiar bumblebee was called a “Dumbledore”.

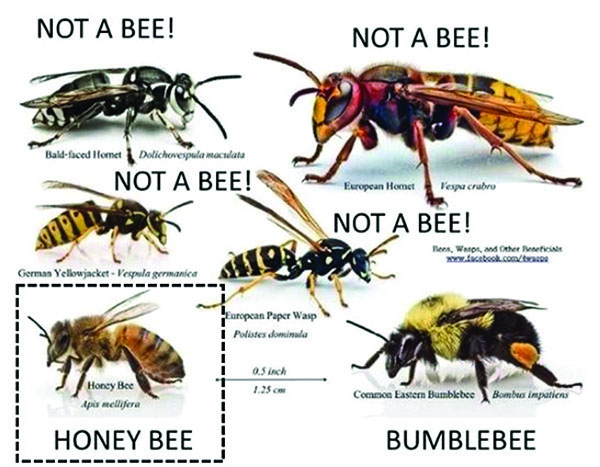

A neat little morsel of trivia that may be, but we will not be talking about Harry Potter, Hogwarts, or Dumbledores by any name. The subject of importance in today’s environment is Apis mellifera and what happens with that, quite a bit less cutesy, critter may, indeed, change your life.

Mellifera (mell-IF-er-ah) is the honey bee and there’s a reason more and more of your neighbors are either keeping or thinking of keeping a hive or two of the bees. Named the state bug in 1974, the honey bee, known for its enormous capacity for work and its fascinatingly complicated biology, has more than once been deemed in danger of extinction.

Bee hives began dying out, called a “collapse”, for reasons no one yet fully understands. Beekeepers around the country began noticing high losses of bees in the winter of 2006. Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), where bees left their hive almost all at once and were never seen again, was soon reported from around the world.

Even wild bees were affected. Various theories arose to explain the deadly phenomenon, from pesticides, fungicides, mites, viruses, habitat loss and climate change, but no particular smoking gun has been detailed.

As word of colony collapses spread, many backyard beekeepers sprung up, often hoping to help the bees survive what looked like an extinction event. According to the state Department of Agriculture, there may be as many as 4,500 people raising bee colonies all over New Jersey, on farms and in backyards.

One of those folks is Ed Ridgeway, owner, with wife, Stacey, of Shepherds Watch Farm on Swedesboro Avenue in Mickleton. He has always loved honey on his morning cereal, he said, and used a lot of it.

“I couldn’t imagine not having honey. Even my wife said I used too much of it,” he said, only half joking. So, in 2010, Ridgeway, a chimney sweep by profession, began a new hobby designed to keep him in honey by saving bees. He bought two bee hives.

“Early on I got stung in the head and had to go to the ER and now I carry an epi-pen. But I haven’t had any more allergic attacks.” What he does have from his first two hives is some 30 or more additional hives.

He and Stacey work the apiary together, dressed in bee suits, and will harvest as much as 1,000 pounds of honey annually. Honey products are sold at the farm store (See: shepherdswatchapiary.com).

Besides the honey, the keeping of hives on this scale is almost a lifestyle. Ridgeway is the keeper of bees and of as much as you ever want to know about bees. For example:

*There are five to 10 thousand bees in any one hive in the winter. In the summer, there are 60 to 80 thousand bees per hive.

*Worker bees, all of whom are female, form a ball around the queen in the winter and vibrate to keep her and the hive warm.

* Worker bees’ life spans depend on the season. They live five to six weeks or so in the summer, when they are highly active. They can live up to six months in winter, surviving on stores in the hive.

*Queen bees can live two to as much as five years and will lay up to 2,000 eggs a day.

*Hives that get too crowded will split, with the queen and a large cohort of workers leaving in a swarm to scout other spaces to build a hive. The remaining workers groom another queen and stay put. The swarm forms around the queen to protect her and if you see one, call a professional to safely remove it. Many beekeepers will do this for free, placing the swarm in a new hive. An internet search will identify bee removal services for Gloucester County.

Ridgeway said he inspects his hives all-year round for dangers, such as Varroa mites, known to harm and eventually kill bees. He uses organic pesticides to control infestations. He also will feed the bees special pollen substitute feed in the winter or when the hives have been unsuccessful in gathering enough food to make honey for the cold season.

Yes. There is substitute bee feed at a store near you, if you know where to shop.

“Time stops around you when you are working with the hives,” Ridgeway said. “There is a quiet calm of movements in the winter, busier in the spring and summer. You get addicted to it.”

That season of movements is also familiar to Dennis Wright, who owns Fruitwood Farms, Inc., on Elk Road, just east of South Harrison Township. He recalled that, “A lot of people were concerned when the population of bees was diminishing. A lot of them got interested in bee keeping and said they would try to help and started hives.”

Wright, however, has always kept bees. His father began with a couple of hives in 1951, he said, and the son took over. Now his farm trucks honey bees from his 4 to 5,000 hives to California to pollinate almond orchards, and to Florida to pollinate citrus orchards. Wright said he sets hives in a number of sections of his 110-acre farm, or loans them out to area farmers, not just to other states.

Then they are trucked back to Wright and let loose to pollinate local crops. He sells his honey products at farm markets in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. See: https://fruitwoodfarms.net/ .

Bees are a necessary part of even today’s modern farming, Wright and Ridgeway both pointed out. The worker bees will fly up to a couple of miles away, seeking a pollen source.

The beekeepers said it is likely there are not many wild honey bees left. Without pollinators, there will be few fruits or vegetables or flowers, and grasses will die out. Insects, already under siege according to recent studies, will have no food source and the birds who prey on insects will go hungry.

Already, Wright said, another danger to pollinators, a nurturing habitat, can no longer be counted upon. “There’s a lot of concrete around here that used to be wildflowers,” he lamented.

So far, local beekeepers are generally prospering, Ridgeway and Wright said. Domesticating mellifera may yet save the species, though no one guarantees any such thing. The apiarists had a request on behalf of the bees, however. “If you see a honey bee in your yard, it might be mine, or another (local) person’s,” Wright said. “Let it be. They are docile and won’t hurt you if you leave them alone, and next spring you’ll have more flowers or fruit because of them.”

He encouraged the trend to keep backyard hives. “If you put a couple of hives out back, they’ll make you 100 pounds of honey.” There are online or in class courses for the beginner beekeeper. Check the website for http://njbeekeepers.org/.

But, as with Ridgeway, beekeeping for many apiarists is only partly about the products. “It’s a common effect to get a therapeutic calm when you’re with your hives,” Wright said, adding, “You get to know the hives, their rhythms. You can find out in a matter of minutes what the hive mood is.”

Such close monitoring of hives and bees and moods by individual beekeepers has aided scientists in studying hive collapse and its possible causes. “A lot of research has been done by beekeepers in the field,” Wight noted. He added the hope that the beekeeping trend, especially if swarms of wild bees are brought into an apiary, will reveal answers to hive collapse. For example, he said, “You might find out there are wild bees resistant to the mites.”

It’s an enthusiastic hope but it runs up against statistics. The numbers show that in the U.S., between 2008 and 2013, the diversity of wild bee population declined by 23 per cent. The decline particularly affected a once-common bumblebee species.

Dumbledore is now on the endangered list.