Bright and happy when she began telling her story a day after surgery at Jefferson University Hospital, Megan Lolly’s composure broke into near-tears in just minutes.

“My husband has held my lifeless body on more than one occasion,” she said, her voice lowering, breaking. “He’s come home to find me not breathing. Not moving. Comatose.”

A pause, a deep breath, and the Mickleton resident, 33, rebounded, eagerly looking forward to her future. She had just received a double transplant, a kidney and a pancreas, that would save her life.

But mixed with the giddy joy of impending health, there is a sadness, Lolly confessed. “I’m getting my life back but that’s through the loss of someone else’s life. I’m a religious person and I am praying for the donor, for his family.”

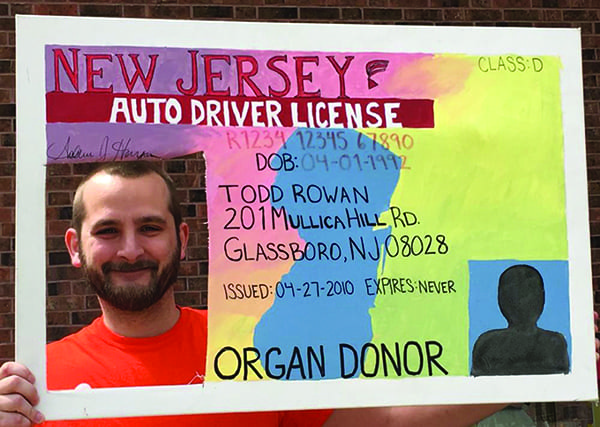

A 31-year-old man from Pennsylvania suffered a brain aneurysm. That man, unknown to Lolly, is her hero. “What he did was put a check in a box (on his driver’s license, signifying he would be an organ donor) and he saved at least three people’s lives. He donated heart, lungs, liver and kidney and pancreas organs,” Lolly said.

The former pre-school teacher and nanny was in end-stage kidney failure after years of battling type 1 diabetes. She had been in dialysis, three days a week, four hours a day, plus dealing with the fatigue and vomiting many on dialysis suffer.

Her best bet, doctors told her, was a kidney and pancreas transplant, since both organs were failing. Her blood pressure and blood sugar levels would spike, leading to seizures, mini-strokes, and cessation of breathing.

Gratitude for the gift of healthy organs underlies Lolly’s recounting of how much the donor’s choice means to her, her family, her future. “I think of him every day. I pray for comfort for his family and for him and I say prayers of thanks that he checked that little box. I think of him as my hero.”

When able, she plans to contact his family to thank them, if they are open to meeting her.

When she’s fully back to health, Lolly said she hopes to become an organ donor advocate, like her friend since high school, Jason Nothdurft. Just 32, the Clarksboro man has a unique perspective on organ donation and a steadfast desire to promote it.

That perspective, desire, and Nothdurft’s expanding knowledge of, and roles in promoting, organ donations began with his childhood friends’ stepfather, Bill Rode.

Rode, 59, of Swedesboro, was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in his 30’s and also with a hereditary risk for high blood pressure. He learned he was in danger of dying while in the hospital nearly six years ago battling pneumonia.

“The nephrologist on staff, Dr. Trina Banerjee, came to me and said I was in stage 3 kidney failure,” Rode recalled. “She saved my life.”

There’s a reason kidney disease is one of those so-called “silent” diseases. It frequently does not show symptoms until major damage has already been done. In Rode’s case, high blood pressure, although controlled with medications, possibly harmed his kidneys. Or perhaps, he suggested, the medicine he took for decades to control the hypertension was part of the equation.

Despite treatment and major lifestyle changes, Rode was in stage 5, which is end-stage kidney failure, a mere two years after diagnosis. “Dr. Banerjee said I had a choice,” Rode said. “Wait for a cadaver kidney or try to find a living donor.”

Dreading the wait for a cadaver organ, a wait many patients do not outlive, Rode chose the latter option. While on the organ transplant list, he decided to seek a living donor through word-of-mouth, social media, and any other venue he could use to make his need known.

“The doctor gave me three to five years of life if I went with dialysis four days a week,” Rode recalled. “I thought I’d seek a living donor. I knew people died while waiting for a kidney from a cadaver.”

Rode realized his long history on Facebook was his one strength in his search. “I had already been talking to everyone about needing help. I could only go three steps in my house before I’d have to lie down. There are 90,000 people every day who need a kidney. I knew I had to maximize my chances.”

Nothdurft, then 27, saw the notice on Facebook that his buddies’ stepdad needed a kidney. He said he never hesitated.

“I grew up in a family that is service-oriented, into volunteer fire departments, other volunteer services. It’s a trait,” he explained. “I grew up in Swedesboro with Bill’s kids. We were close in school, sports. I knew they had lost one father. I didn’t want them to lose another. I knew I had the resources to do this. I had just started dating a wonderful girl (now his wife, Rachel) and had a good job. I had absolutely no doubts and do not regret my decision one bit.”

With no second thoughts, Nothdurft took four weeks sick leave from his job as a police dispatcher with Gloucester County to undergo testing in 2014 as a possible donor for Rode. He was one of seven people, two of whom were Rode’s stepsons, to volunteer a kidney.

The testing determines much more than matching blood type and various other cogent medical considerations. Potential donors are checked for health, for whether there has been pressure applied to get them to volunteer or payments promised, for their understanding of the procedures involved and the recuperation time needed.

“I went through a lot of medical evaluations and at every stage you are given the opportunity to back out for any reason because it’s OK to change your mind.”

It is pretty much major surgery to donate an organ and recuperation time can be up to a month or more. The medical costs to the donor are paid by the recipient or, generally, his or hers insurance. Nothdurft said there were some tough times but his preliminary testing comforted him. “They told me I could live with one kidney for a long life following a healthy lifestyle.”

Of the seven volunteer donors, his was the best match and the transplant has been a success. It has not been cheap for Rode, however. “This is the part people don’t hear about,” the kidney recipient said. “I had to stop working when I was sick.

Rode was a successful entrepreneur of local eateries. “I had to sell my house, and my wife, Kathy, and I moved in with her mother,” he said. “It shouldn’t be this way.”

Nothdurft grew close to Rode and began to see the barriers in the path of people needing an organ transplant. He began advocating on a volunteer basis and has become well-known in advocacy circles for his tireless work and enthusiastic efforts. It is practically a second career and perfectly suits his need to be of service.

“I volunteer with the National Kidney Foundation as a part of their Kidney Advocacy Committee. I am also an Ambassador with the American Association of Kidney Patients,” Nothdurft said, adding he was happy to be uniting his education and passion.

“I joined these organizations because I have a degree in political science from Rowan University and have some experience with legislation from when I was an intern with the state legislature. It was a perfect opportunity to put my education and experience to good use.”

The organizations and Nothdurft concentrate on three main goals in their advocacy:

1. Increase funding to fight kidney disease, enhance research, and increase early detection.

2. Mandate that Medicare covers an organ recipient’s anti-rejection medication forever instead of just three years. This would prevent kidney patients from going back on dialysis, which costs a considerable amount more per year.

3. Make organ donation covered by the Family Medical Leave Act and prevent the insurance industry (health, life, long term care, etc.) from discriminating against living organ donors.

He has lobbied state and federal legislators on the issues and the needs of the approximately 30 million people in the country living with kidney disease. In addition, Nothdurft posts stories and information on his work to educate about the desperate need for organ donors and the needs of organ recipients.

He helps people seeking living donors learn how to ask for help and urges people wanting to become a donor to make out a living will to that effect and to check the organ donor box when getting a driver’s license. In the event of death, the license will alert police or medical staff to honor your wishes.

There is more to the value of organ donation than extending the life of a person who would die without one. Not just quantity of years is affected for the better, so is quality of life and every recipient understands the immense magnitude of that gift.

Megan Lolly tried to explain. “I’ve been a diabetic since I was 13 and I’ve had a hard time of it, of controlling it. I took insulin shots three to five times a day. I was on dialysis and got sick as a dog every time.

“Now my life is changed. I don’t have to take insulin anymore, dialysis. I don’t have to be sick. My husband’s life changed, too. He doesn’t have to worry what he’ll find when he comes home,” Megan continued.

“I’m no longer in kidney failure,” she said, wonder and disbelief in her voice. “I will be able to have a full life once again. The quality of my day to day life is already filling up. I no longer take insulin. I am no longer a diabetic,” she said slowly, wanting her words to resonate.

For the second time in the interview, Lolly choked on sudden tears. “And all because a hero checked that one little box.”

Nothdurft said people are “more than welcome” to contact him about organ donation and kidney disease by accessing him at Facebook: https://facebook.com/JasonANothdurft/ or on Twitter: @j_nothdurft

Most states ask drivers getting licenses to check a box if they wish to be organ donors. Police, ambulance staff and doctors check licenses when death occurs so proper procedures for saving organs and honoring the donor’s wishes can be followed.

By Jean Redstone